The Only Man with Three Memorials at Holy Trinity

- Admin

- Sep 5, 2024

- 14 min read

Updated: Oct 30, 2024

Judit Kiraly shares an extract from her book "The British Suburb of a French Resort", explaining the involvement of the Lacroix family with the British community in Nice

Adolphe Lacroix was not a clergyman, he was not born British nor of royal blood and not even of noble origins, yet he has a fabulous memorial window on the south side of Holy Trinity, a remarkably beautiful lectern purchased by the congregation engraved with his name, and in the cemetery he has an elegant portrait engraved on his tombstone which is situated near ‘his’ memorial window. Special permission from the Prefecture had to be given for him to be buried here in the cemetery since burials were no longer allowed; but it was inconceivable for the congregation to bury him anywhere else but here.

Why would he be so honoured? His story is that of the Lacroix family. It is an entire family and not only Adolphe; a family which for seven decades represented and worked on behalf of the British community and were British Consuls in Nice. This is a simplified history of three men from the same family; all three were known simply as “Consul Lacroix”.

From 1819 to 1884, first father Pierre and then his two sons Adolphe and Albert looked after the rapidly expanding British community, handling the various political, commercial and diplomatic issues that marked a century of important British presence in Nice. These were complicated decades, especially in Nice.

During my years of doctoral research, I learned to appreciate clearly legible handwriting. Researching the history of the Anglo-American community led me to the UK Public Record Office in Kew, where huge bound volumes hold “Consular Reports” from all areas of the world. Once I figured out the ‘where is Nice filed’ question (catalogued as Italy, Sardinia or France depending on the year because Nice belonged to the House of Savoy until its 1860 annexation to France) I finally got to read the actual files and learned to appreciate the neat and tidy handwriting of Consul Pierre Lacroix. His Consular Reports were simple, precise and carefully constructed.

In those early days, when communication and correspondence was a time-consuming issue and the consulship not particularly well paid, being the British Consul in Nice was not an easy appointment.

In the years preceding Holy Trinity’s construction, the Lacroix family was already active. We have the copy of correspondence with Intendent Crotti regarding the requested cemetery concession which is dated 1821. Dr William Farr, a medical statistician wrote about the early days of the Lacroix Consulate (the1840s) in his Medical Guide to Nice; as Farr is a very reliable source, I cite here a section from his book about duties:

THE CONSULATE

The last regulations for defining the duties and perquisites of the British vice-consul were enacted in 1826.

The power of appointing the officer and determining the salary rests with her Majesty. The office is held for life, unless forfeited by accepting, in the execution of his duties, any fees not herein named, in which case he, for the first offence, forfeits any sum not less than the twelfth part or more than the whole of his annual salary, at the option of the court where the penalty is recovered; and for the second, he forfeits his office, and becomes ever after incapable of serving her majesty in any like capacity. The vice-consul is authorized to relieve distressed subjects or mariners who resort to him, to administer oaths and affidavits, and to perform any of the duties of a notary public. He is entitled, at the option of her Majesty, to a superannuation allowance after ten years' service.

Reading the BRITISH CONSUL’S MANUAL, written by E .W. Tuson (1856), more details about the duties of a Consul emerge, namely providing representation on a diplomatic and political level, dealing with the local authorities and with the needs of the local British residents and visitors, and most importantly the Consul had to represent British interests commercially; Trade and Commerce were the magic keywords in a Consul’s duties.

The original British Commercial Treaty with Turin (which included Nice) dated from 1834. In the individual correspondence cited for each Lacroix Consul we see the extent of the extraordinarily detailed information they had to furnish about certain commercial questions in order to increase the possibilities of trade and commercial ties with Britain; this was the primary reason for their appointment. For their work they received an annual remuneration, although Nice was not highly valued as a commercial port. In comparison with the various salary levels allotted to British Consuls in Europe, Nice (Sardinia) had a paltry annual consular salary of a mere £200 which was less than Marseille (£550) or Genoa (£400 ) which were both more important commercial ports. This salary would be increased in the years to follow as the amount of work grew with the increasing number of winter residents in Nice and the increase in commerce, but above all due to the strengthening of political ties.

In a letter of 14th October 1824 addressed to King George VI, George Canning requests an immediate increase of the salary of Mr Lacroix as meritorious:

Mr Lacroix was appointed to that situation by your Majesty’s Consul at Genoa and approved (as is usual in the case of Vice Consuls) by the Foreign Office. But although Mr Lacroix’s nomination has been this in the usual course, the duties which he has had to discharge are of such a nature and the manner in which he has discharged them is, by the testimony of many of your Majesty’s subjects shown to have been so meritorious, that Mr Canning has no difficulty in humbly recommending to your Majesty that your Majesty’s Minister at Turin should be instructed to pay to Mr Lacroix an allowance of £250 a year; the same to date from January last in order to cover any expenses (sic) which he may have incurred and not brought to account.

Source: Letters of King George VI by A. S. Aspinall

The Lacroix family originally were bankers before father and sons respectively became Vice-Consul and later Consul. It was with great surprise that I learned from a Foreign Office List from 1865 that in fact there were three Consul Lacroix and not only two as I had originally thought (please note that the name is split into two and that Pierre in anglicised into Peter). There are also some documents where they are erroneously called Delacroix. They are in alphabetical and not chronological order in this document. Here is the exact text:

LA CROIX, Adolphus, was Vice-Consul at Nice from July 28, 1819 to July 22, 1842, when he was appointed Consul at that Port.

LA CROIX, Albert, was Acting Consul at Nice from August 11 till September 12, 1864

LA CROIX, Peter, was appointed Vice-Consul at Nice, September 18, 1819 ; and Consul there, September 20, 1825, which post he held till July 1842; was Acting Consul from May 18 till September 4, 1858 , from August 21 till October 8 1859, from July 25 to September 22, 1861; from August 1 to October 1, 1862 ; and from August 13 to September 17, 1863.

These dates seem to be very confusing and need an explanation. Whenever, a Consul or Vice Consul was absent another person received a temporary appointment for a short period to act as replacement. This explains why in retirement Pierre again and again became Consul while his son was already Consul, but was probably away on leave. Adolphe was replaced in his duties both by his father Pierre, and later was also replaced by his brother Albert.

As we said the family business was not only consular but financial too, therefore the first British Consular Office was next door to the Bank Lacroix which was a rather small bank in comparison to the important Avigdor and Carlone family banks of Nice. Though respectable, the address was not very prestigious or fashionable either: 8 Place St Dominique.

Pierre (Peter) Lacroix (1787-1864 ) received his first appointment in 1819. His evolution from being a nondescript Vice-Consul to being a well-respected friend of the greatest names in politics and the European elite is simply astonishing; when he started his work he probably never imagined the social importance he would gain. I couldn’t find where he learned such excellent English. His handwriting is precise and both his French and English correspondence point to a very well-educated man.

He was born in Nice and lived here all his life. His wife had the unusual name of Marie-Anne Nata, but we don’t know about her background. They had a large property in the suburb of St Barthelemy where there was a hot-water spring, which was often mentioned in various Travel Guides as worth a visit. Joseph Natta of the same address (but spelt with two t's) was possibly a brother-in-law. Again it is a bit of mystery as to how Joseph became the official correspondent of the English Murray Guides, but in any case he had to speak English to be able to do his job.

As the number of British residents in Nice over the winter months grew during the early 1830's Pierre Lacroix’s daily work correspondingly increased further. Among the duties he was required to carry out was regular correspondence about the availability and prices of goods. I copy here one of his earlier reports:

Copy of a DISPATCH from Consul Lacroix, dated Nice, 1st October 1826

To John Bidwell, Esq.

Sir,

In reference to your Circular Letter dated 29th, I have the honour to transmit to you the Account of the Prices of the several sorts of Grain and other Articles, the raw produce of agriculture of this country, free of all charges, as paid to the farmer during the preceding three months; I beg also to forward, an Account of the Average Prices of Wheat in this district from the present time back to the year 1707, being the latest period to which I have able to procure accurate information.

Adverting to Mr. Canning's request to procure and transmit to him an account of the quantities of the several sorts of grain exported annually from ports of this district, I beg leave to observe, that in consequence of this being a very hilly country, and entirely occupied by olive plantations, the produce of wheat is not equal to the consumption, and there is therefore none exported.

I have the honour to be, (signed P. Lacroix)

Source: House of Commons, Papers, 1827

Nice was a particular case as monies, measures and standards were different from those used both in England and France and Consul Lacroix sent detailed specifications about this matter. Below is an extract from the Universal Cambist and Commercial Instructor, by Patrick Kelly (1821), a sort of a handbook for bankers and commercial houses that quotes Lacroix’ explanations:

The monies and coins of Nice are the same as those of Turin. The weight for gold and silver is the Poids de Marc. The commercial Pound is composed of 12 Ounces, and is equal to 4809 English Grains. Thus 100lb. of Nice correspond to 68,76lb. avoirdupois, or 31,16 Kilogrammes. 2511). make the Rubbio, and 6 Rubbi the Quintal. Corn is measured by the Charge, which is divided into 4 Setiers, 8 Emines, 16 Quartiers, or 64 Motureaux, and equals 1,6 Hectolitre, or 4j English Bushels.

(The above is extracted from the dispatches lately sent to Lord Castkreagh with standards, by P. Lacroix, Esq. the British Consul at Nice).

Pierre Lacroix did a remarkable job managing the delicate British purchase of land for the first villa-church and all the associated correspondence with the local Syndic (mayoral office). Peter’s son Adolphus Louis Lacroix (1817-1871) was the longest standing British Consul in Nice where he worked for over thirty-seven years in the interest of the community and in the interest of Holy Trinity. Recently a manuscript signed by Queen Victoria together with the Royal seal came on the market. I cite the contents as it is the nomination document of Adolpe Lacroix:

July 18, 1845. Also signed by Foreign Secretary George Hamilton-Gordon, 4th Earl of Aberdeen.

Queen Victoria, for the encouragement of Our Subjects trading to Nice...agreeable to the friendship and good correspondence subsisting between Us and our Good Brother the King of Sardinia appoints Adolphus La Croix, the United Kingdom’s consul at Nice.

(The price asked for this document was £500 to 750,we have no idea who could have put it up for sale on the internet, possibly not a descendant of the Lacroix family.)

What do we know about Adolphe Lacroix? His English was understandably excellent, for his father sent him to England to be educated. His wife Frances (Fanny) Jane Myrton Cunynghame was also British and came from a prestigious aristocratic family. They married in July 1844, and we know that to marry he converted to the protestant faith. They lived in the Villa Marie-Louise in fashionable Cimiez. Adolphe was on excellent terms with the Reverend Childers and he was an important member of the Church Committee.

In reality a duo of Consuls was working in Nice because father and son would sign documents sometimes simply as ‘Lacroix’ and it is not always evident which one of them is the signatory. Adolfo addresses the Municipality about a road problem in 1846 in Italian. Adolphe corresponds with the Foreign Office in English and in town he speaks French and Niçois; he was a very versatile linguist.

With the impending 1860 Annexation the subject of correspondence became more and more oriented towards political issues, though he still furnished the regular commercial reports.

In 1860, Consul Lacroix was a very busy man; his missives to London are frequent, almost daily dispatches as the Foreign Office wished to be informed about everything concerning the French takeover of Nice. This was of the utmost political importance as it concerned a Mediterranean trade port

Consul Lacroix to Lord J. Russell received March 2 (extract)

Nice March 17 1860: I have the honour herewith to enclose a copy of a notice published yesterday in the “Gazette de Nice”.

This document emanates from four gentlemen representing the Municipal Junta at Nice

Adolphe Lacroix sent a day-by-day account summarising local feelings and newspaper articles about the vote and lack of interest regarding the question of the Annexation of Nice. He judged the local attitude concerning the results by these surprising words: ‘the voting was received very coolly by the inhabitants ‘.

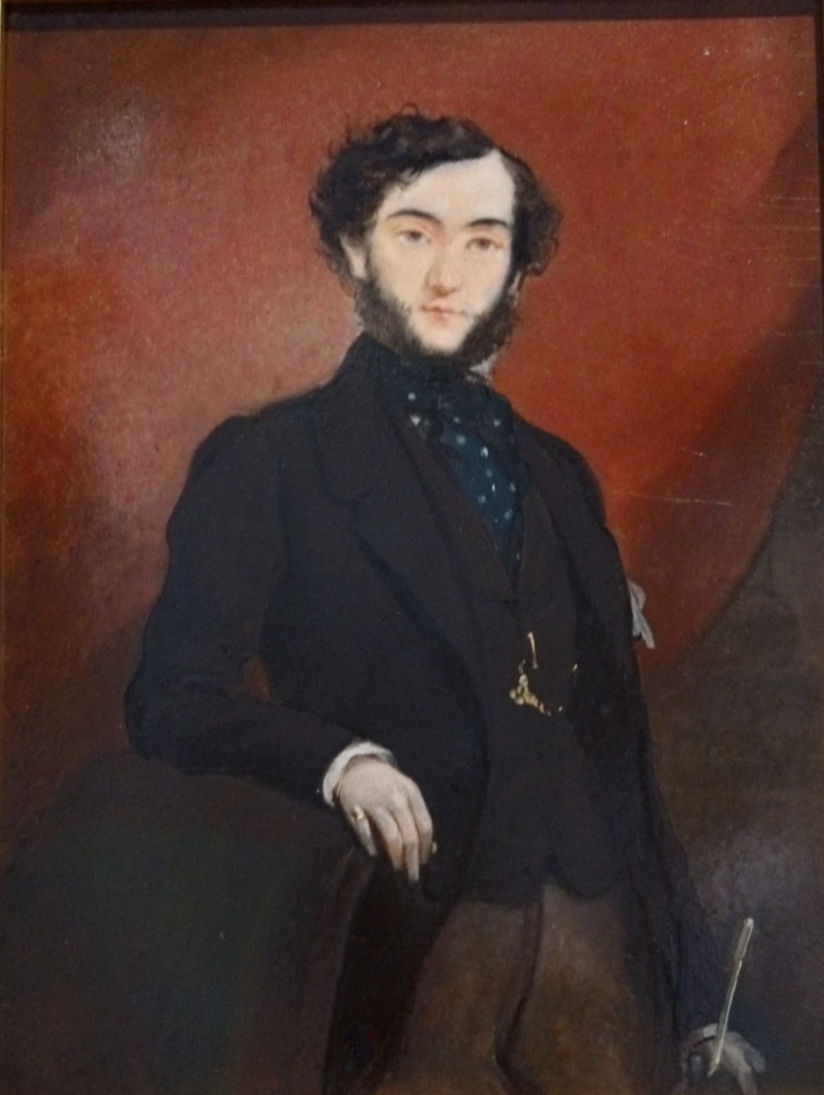

He had British interests at heart and curiously he sported a British look as well. We could find no photographic image of him, though there is a painted portrait of him. This carved marble profile is taken from his grave (see below for the facial similarity with his brother Albert).

Besides the requests for increased political information his duties remained varied. Adolphe was expected to be an expert in many fields and in anything that might yield commercial results. To give an idea of this I quote here from The Technologist (1866) by P.L.Simmonds that cites an extract from one of his dispatches:

Report by Consul Lacroix, Nice

Notwithstanding the rich resinous forests which cover the Maritime Alps and also a very large extent of the adjoining Department of the Var, no industry exists in this place or its neighbourhood for collecting the resinous juice from the different species for trees which form these forests.

Pierre Lacroix had to also act as a moderator between Turin’s Catholic authorities and the congregation of the British Protestants, which was on occasion a tightrope dance. Even the slightest decision took months to get confirmation from Turin and then it would still be debated again in the Nice Senate. The question of the new Protestant Cemetery in Nice took years of correspondence between Nice and Turin before final authorization was given. The question of personal documentation was even more complicated. Three languages and two religions can really lead to a Consul being overworked, as documents were laboriously handwritten. He had to provide official documents, certify births and marriages, issue travel documents and deal with customs duties and give certificates and references for tradesmen and servants. These documents are in Italian, French and in English and sometimes the same document is produced in all three at once; a lot of handwritten paperwork!

Registers were a nightmare to handle. In 1838, he requested the right to have proper church registers for the British residents but received only partial permission and the situation remained a bit confusing regarding birth, marriages and death certificates for the British in Nice. In the Archives Departementales in Nice the birth and death registers are by ‘paroisse’ (parish) until 1860, then after 1860 they are combined in the Etats Civil, but the British already had a separate register only for its use to be interrupted for some years during the French occupation of Nice. It can be a very sad read as the number of deaths registered vastly outnumbers the births and baptisms registered. In the English registries there were also noted the Vaudois Italian baptisms and surprisingly, the occasional Russian and German birth too; after all, they couldn’t be entered into the catholic parish registries.

But there was also another reason for this: Lacroix was wearing two diplomatic hats at the same time. Pierre Lacroix was not only dealing with the British, but with the Germans too. He was also Consul for Hanover and a highly decorated part of their diplomatic system. It is at the same address that we find the two Consulates as well as the Bank ran by this energetic team of father and sons. Adolphe died unexpectedly, leaving no male heir. This portrait of Adolphe Lacroix, British Consul at Nice, hangs in the Musée Masséna (please note the pen in his hand… he undoubtedly used it all the time).

I was a bit surprised when paging through a book about the history of the Caisse d’Epargne bank in Nice when I came across this detail of their bank: that Fanny Cunynghame Lacroix continued to maintain the Lacroix Bank after the death of her husband Adolphe, but under the name of Banque Veuve Lacroix (and their daughter then continued the work until her death in 1896). The bank was finally taken over but she had kept it going for a good couple of years, meaning that she had remained in Nice. The bank was finally sold in circumstances as peculiar as they sound: ‘aux enchères’ to the highest bidder. Their daughter, Frances (1855-1912) married a maltster called Mr Whalmsley in Kensington; they had two children who unfortunately both died young. The other daughter Louisa Lacroix, married an American.

Adolphe Lacroix’s beautiful grave in the churchyard started to tilt sideways so during the 2012 renovation of the church it was stabilised. His portrait is a remarkable work of marble carving. Curiously, he stipulated that he wanted a simple family burial but the community was notified only afterwards.

We can compare this image in marble to that of his brother. Unfortunately, we found no image of the father Pierre Lacroix, but there is a bust of Albert Lacroix.

We know very little about Albert (1830-1912) except that he was a banker too, working in the family business and on occasion as a replacement Consul. He was in the local news once because he contracted a highly publicized marriage in June 1862 with the Russian (Ukrainian) Princess Vera Havansky. This British/ French /Russian society marriage had an unusual witness: Charles Bailie Hamilton, M.P. for Aylesbury, who was a personal friend of Pierre Lacroix.

Both the bride and groom were over thirty years old, a little unusual for the epoch when people married fairly young. The Havansky family was a very wealthy aristocratic family who came to winter in Nice and Vera fell in love with their banker. It was an excellent marriage for the Lacroix family’s social status but the marriage came to a very sad end when Vera died a year later giving birth to twins. One of the twin daughters Zeneîde also passed away three weeks later. Alfred thus became a widower with a baby to care for. The surviving twin baby Anna Vera Havansky Lacroix added an even more illustrious name to the ones she already possessed, when in February 1885 she married Comte Charles Gilletta de St Joseph. The marriage was a success and they had seven children; she is buried in the Chateau cemetery above Nice. The Count came from a large, local noble family and was Mayor of Eze for a while.

The fabulous Lacroix memorial window is on the South side of the church. It is the design of the famous Scottish stained-glass maker and art dealer Daniel Cottier but the realization was probably carried out by his master-verrier Vincent Hart; it came to Nice by train and was assembled here. This photo shows the rich colours so typical of Cottier windows because it is taken in full sunshine from the south (there are another two Cottier windows in Holy Trinity). The style is Pre-Raphaelite and seems very modern in comparison to the Mayer of Munich windows nearby.

The Lacroix family were protectors of British citizens, their interests and political status. They were devoted and excellent consuls and obviously very much appreciated and loved by the community. This explains the tomb, the window and the lectern recalling the memory of Consul Lacroix, and as we said he is the only man with three memorials at Holy Trinity.